🍄 Reverse Mythology: The Legend Returns

AI is decoding archaic texts, myths are being repurposed to help navigate modern challenges and heroes survive through ancient script to screenplay.

Exploring every rabbit hole there is. For more wanderings, become an Alice in Futureland subscriber—it's free.

🍄 AudioDose Alice on Sonic Mushrooms: listen to Metamorphosis

🎧 Alice podcasts

📘 Alice books

Hello, we’re Alice and we are always in a state of wander. A long, long time ago, before Suzanne Collins wrote The Hunger Games, came the ancient Greek tale of Theseus and the Minotaur. To punish Athens for the death of his son, King Minos of Crete demanded a tribute of seven maidens and seven youths, drawn by lot, every nine years to be sacrificed to the Minotaur monster. “There is no such thing as a new idea,” Mark Twain once wrote. “We simply take a lot of old ideas and put them into a sort of mental kaleidoscope. We give them a turn and they make new and curious combinations.”

Legend has it that mythology lives on everywhere around us, from Marvel movies to The Matrix. Ancient symbols surface as the Starbucks Siren and Ulysses is reborn as an Australian butterfly. The Greek goddess Artemis—twin sister of Apollo— inspired humanity’s most advanced antics yet: NASA’s new mission to the Moon.

And mythical cities rise from the ashes. While extensively name-dropped in the Bible, Babylon was actually only discovered in the mid-19th century. Found near Bagdad, Iraq, Babylon was the capital of southern Mesopotamia (the region now known as the Middle East), and home to some of the earliest known human civilizations.

More recently, the deadly tsunami in the Indian Ocean on December 26, 2004, revealed the truth of the legend of Mahabalipuram, a port city on India’s northeast coast, said to be home to seven pagodas. Smithsonian Magazine reports that the powerful tsunami removed centuries of sediment from the ocean floor just off the coast, revealing several submerged temples.

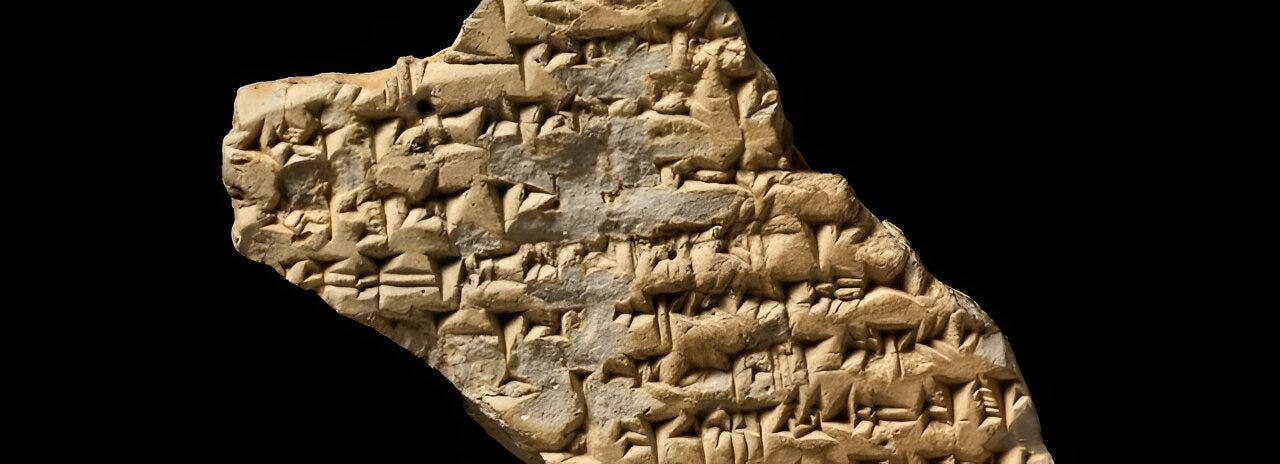

Predictive ancient text

At the British Museum in London, artificial intelligence (AI) helps piece together an ancient Mesopotamian script. Computers are being trained to read and translate cuneiform, the ancient script carved into clay tablets. Fragments from the same tablet can be scattered around the world. “There’s a tablet where there’s a piece in Chicago, which joins a piece in Berlin and a piece here,” Irving Finkel, assistant keeper of ancient Mesopotamian script, languages and cultures at the museum, tells New Scientist. With development in AI, museums are now able to put fragmented tablets back together and even predict parts of missing text. From shopping lists and prayers to customer complaints, “people say the first half of human history is only recorded in these cuneiform tablets,” says Enrique Jiménez at Ludwig Maximilians University in Munich, Germany.

Speaking of myth-tech …

… Historians show how ancient myths actually envisioned and invented modern technology. ‘The first robot to walk the Earth was a bronze giant called Talos,’ writes Adrienne Mayor in Gods and Robots – Myths, Machines and Ancient Dreams of Technology [Princeton University Press, 2018]. “This wondrous machine was created not by MIT Robotics Lab, but by Hephaestus, the Greek god of invention.”

Mayor, a Stanford research scholar in classics and history of science, calls Alexandria, Egypt, the “Silicon Valley of antiquity,” where inventors designed complex automatons, self-driving theaters and grappled with ethical concerns about biotechne, ‘life through craft.’ “As early as Homer, Greeks were imagining robotic servants, animated statues, and even ancient versions of Artificial Intelligence,” writes Mayor. “While in Indian legend, Buddha’s precious relics were defended by robot warriors copied from Greco-Roman designs for real automata.”

Meanwhile stories set light years in the future, are still rooted in the past.

We need a hero

From Star Wars to Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, it’s impossible to un-see the “hero journey” once you spot it. Films frequently plot around a mythological storytelling structure popularized by the later American writer Joseph Campbell in 1949. “There is what I would call the hero journey, the night sea journey, the hero quest, where the individual is going to bring forth in his life something that was never beheld before,” he wrote in The Hero with a Thousand Faces. This ‘archetypal hero’ shows up everywhere now from The Lion King to The Lord of the Rings. Which is of little surprise, since Campbell hypothesized that human stories do not change because humans themselves do not change.

“The stories we tell reflect who we are, as both individuals and societies, at any given time,” writes author Lizzie Enfield for the BBC Culture. “Reading stories from centuries past, it's reassuring to discover that while times change, human instincts and emotions are more constant and universal. The joy of reading is to commune with other people through the stories they have left behind—but to recognize in their worlds something of our own.”

Norse code

Take Thor, writes Enfield, a prominent Norse god associated with the protection of humankind, and a model for the latter-day superhero. ‘Reinvented by Marvel Comics as the Mighty Thor, the hammer-wielding hero who patrols the borders of the human world and keeps the giants out, he is echoed through Superman, the Hulk and other Avengers.’ She speaks to Carolyne Larrington, author of The Norse Myths that Shape the Way We Think [Thames and Hudson, 2023] for BBC Culture. “What's interesting is that from the old Norse myths what remains is bit of a bonehead who hits people with his hammer first, and asks questions later," says Larrington, a professor at Oxford University. "What Marvel has done has given him a learning curve by putting him in a family where he has relationships with and adoptive brother and father and where he falls in love, so that his superhuman strengths are tempered by his human flaws."

Larrington explores the contemporary resonances of Norse myths, and examines their reimagining in popular culture. "The Norse myths are important because they take place in a landscape which for people in Britain and the English-speaking world, we recognize as being like our own. And unlike Greek and Roman myths, they portray a world which is finite. Its inhabitants are marching towards the end of time. So they have a note of pessimism which resonates in a more secular world."

Myth, reinterpreted

In Poland, Prof. Katarzyna Marciniak at the University of Warsaw, is producing an educational mythology program to help teenagers tackle today’s challenges. “The Modern Argonauts” has been funded by a European Research Council (ERC) Proof of Concept grant and will help young people understand and discuss current themes through myths, for example, Troy for war, Aeneas for migration, and Medusa for womanhood.

Mythologies can be used as a tool for dialogue. “We look at a given problem from different perspectives by studying the classics and mythology — for example, the myth of Prometheus in Mary Shelley's novel Frankenstein (1818),” she tells Academia-net.org. “We all know the story about a scientist who uses the latest technological advances to create a human being. Dr. Frankenstein's monster is a cultural icon, also widely present in works for young people. But where is Prometheus, the Titan, considered to be the benefactor of humankind? It is rarely remembered, but Frankenstein has the subtitle The Modern Prometheus. Shelley consciously referred to the myth of this Titan in a negative context, already known in antiquity – of a Prometheus committing the sin of hubris and overstepping the boundaries set by Zeus. She thus wanted to draw attention to the dangers to humanity brought by the Industrial Revolution. Dr. Frankenstein, the maker of the creature, violated the laws of nature and paid a terrible price. This fictional tale and its mythological references resonate particularly strongly in our own times as we become ever more aware of our responsibility for the possible consequences of progress.”

A global warning

That’s not the first time Zeus got angry. The Greek myth of Phaethon could be said to portend climate change and global warming. Phaethon, who had lived with his mother, swore to prove to his peers that his father was Helios, by driving the sun chariot across the sky—an act that even the gods were uncapable of. Helios was so pleased to see him he promised to grant his son a wish. Phaethon asked to drive the sun chariot across the sky for a day – a request his father disapproved of but dutifully did anyway. He advised him against all the dangers and demanded he must never use the whip. Phaethon whipped away and the horses went wild, causing him to lose control of the sun chariot, wreaking havoc in the sky and the Earth. The gods managed to spare the Earth from further disaster, and the planet’s slow road toward recovery had begun.

Some philosophers and theologians argue that today, just like Phaethon, humans have deluded themselves into believing that they’re able to take advantage of their free will and control the ‘reins’ of nature, even if it means polluting the Earth to such a point of destruction.

Lore and order

Myth is much more important and true than history. History is just journalism, and you know how reliable that is.—Joseph Campbell

Campbell famously outlined the ‘four functions of myth’ in The Power of Myth [1987]. “Myth opens the heart and the imagination to the wonders of the universe and the mystery of existence,” he said, explaining the first ‘mystical’ function. The second is cosmological, that we “haven’t got all the answers.” Sociological is the third, to support or challenge certain social norms and orders. The educational fourth function is ‘psychological (or pedagogical)’ and serves to guide an individual through stages of life, within the context of that culture.

“Myths do not serve their symbolic function unless they are internalized by someone; only then can they provide guidance and unification,” argued philosopher Michael Zimmerman in a 1988 essay for SUNY Press. “Although sometimes dismissed as merely fictitious narratives of supernatural characters, myths play a basic role in human existence, often even for people who claim to live life wholly ‘rationally.’”

Mythology ever after?

“The real purpose of myth is not to present an objective picture of the world as it is, but to express man’s understanding of himself in the world in which he lives,” wrote the late theologian, Rudolf Bultmann, in Kerygma and Myth [1953.] “Myth should be interpreted not cosmologically, but anthropologically, or better still, existentially ...”

To which Philip Ball, author of How to Grow a Human: Adventures in How We Are Made and Who We Are [University of Chicago Press, 2019] responds:

“If this is indeed at least a part of what myth is about, then myth-making can cease only when ‘the world in which we live’ has ceased to change, and when we have solved all of our problems and resolved all of our anxieties.”

When we lose our myths we lose our place in the universe.

—Madeleine L'Engle, author of A Wrinkle in Time

What else we are wandering…

🔍 Curiouser and curiouser!

“Lewis Carroll's fairy tale about a young girl's descent underground is literally the oldest story in the world,” writes David Day, author of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland Decoded [2015, Doubleday.] Day, who spent 18 years down the rabbit hole studying the Lewis Carroll classic, says that the fairy tale is based on the story of the Mesopotamian goddess Inanna’s descent into the underworld realm of the dead. “It is the oldest recorded myth in world literature and one that is retold in the Babylonian myth of Ishtar and the Egyptian myth of Isis,” writes Day. “The story is best known as the Greek myth of Persephone, the goddess of spring whose descent into the underworld was one of the most popular mythological motifs in art and literature throughout Carroll's lifetime, indeed the entire Victorian age.”

📘 Give me a sign

Symbols and Myth-Making in Modernity [Anthem Press, 2022], a book by Ali Qadir and Tatiana Tiaynen-Qadir, investigates the metaphoric power of symbols in human imagination today and in the past. “In this refreshingly innovative work, the authors incisively relate the mythical themes in popular films such as Matrix, Moana, and Pirates of the Caribbean, among others, to ancient mythemes,” writes Dr. Frederique Apffel-Marglin, Professor Emerita of Anthropology, Smith College, Massachusetts. “They reveal the link between ancient myths and the themes foregrounded in this type of film. More importantly and revealingly, they show how modernity’s aversion to ambiguity, multivalence, and especially to interior transformation leads to a situation that has produced fragmentation. Fragmentation modernity generates both at the level of the individual and at the societal level. This situation has given rise to epidemic levels of mental illness and drug addiction in modernity as well as to a deepening of political fragmentation and ecological destruction.”

The book traces how ever-present cross-cultural symbols, residing in ancient rites, masterpieces of Renaissance, Sufi poetry, religion and myths, erupt in popular culture today, including in cinema, books, visual art, music and politics.

✨ Dream sequence

Yoko Ono said: “A dream you dream alone is only a dream. A dream you dream together is reality.” Joseph Campbell goes deeper still. “Myths and dreams come from the same place. They come from realizations of some kind that have then to find expression in symbolic form…a dream is a personal experience of that deep, dark ground that is the support of our conscious lives, and a myth is the society’s dream. The myth is the public dream and the dream is the private myth. If your private myth, your dream, happens to coincide with that of the society, you are in good accord with your group. If it isn’t, you’ve got an adventure in the dark forest ahead of you.”

Craving more?

📘 Alice in Futureland books

🎧 Alice in Futureland podcasts

Thanks for tuning in.

For more wanderings, become an Alice in Futureland subscriber—it's free.

Invite your friends to this mad tea party and let's see how many things we can learn before breakfast.

©2024 Alice in Futureland